WHY PATERNAL LEAVE MATTERS FOR EVERYONE

This reluctance to encourage men to take paternity or parental leave is puzzling when you consider the way everyone benefits when they do. Men, their partners, their children, and their companies are all more likely to thrive if men spend time with their children in the time after their arrival. Here some of the ways:

It’s better for men.

Studies show that father-and-baby bonding during paternity leave actually improves a dad’s ability to care for children in the long term, enabling him to be a more engaged and involved parent. Paternity leave also has a positive impact on men’s relationships. In Norway, following the introduction of a four-week paternity leave, a study found an 11% lower level of conflict over household division of labor. A study in Sweden found that couples were 30% less likely to separate if the father took more than two weeks off to care for a first child. Another study even showed that higher level of participation in paternity leave was associated with lower mortality in fathers with depression.

It’s better for women.

Paternal leave is hugely impactful for women, both at home and at work. When men take parental leave, women see a decline in overall levels of post-partum depression and sick leave, and increases in well-being,

At work, the benefits are even more stark. Women at work suffer from what is known as the “motherhood penalty.” Research shows that hourly wages of mothers are approximately 5% lower relative to childless women, that they are 79% less likely to be interviewed and hired, and that they are offered lower wages when they are hired. Mothers are also half as likely to be promoted. However, when spouses take leave, a recent study found, women’s salaries on average are approximately 7% higher for every month of leave men take. In fact, each month a father is on leave has a greater effect on maternal earnings than maternal leave does, according to that study.

If men are encouraged to take the same leave that women do—allowing them to shoulder similar responsibility for child caregiving—it creates a level playing ground and expectation, in which the disproportionate penalty on women’s pay and advancement opportunities could be mitigated.

It’s better for children .

Children whose fathers take parental leave also benefit from having Dad at home in their first weeks. Kids whose fathers take paternity leave show better developmental outcomes, improved performance in school, and improved cognitive scores and mental health outcomes as they grow older.

It’s better for companies.

Companies may stand to gain the most from encouraging men to take parental leave. Between 89% to 99% of employers say leave has no dispositive effect on productivity, profitability, turnover and morale, according to one study. According to studies in both Scotland and the U.S., fathers and parents of both sexes who received parental leave were more likely to stay with their companies. In Quebec, a study has shown that paternity leave is associated with a mother’s ability to return to the same employer—a significant advantage to companies hoping to keep good talent—provided the practice becomes widespread.

Perhaps most importantly, paternity leave is proving to be the key to addressing the pay equity gap. Because working mothers are still doing the bulk of the parenting work at home, their upward mobility in the workplace is hindered and they fall behind. By allowing men to help shoulder responsibility from the start we can help equalize the effects of maternity leave and motherhood on the development, compensation and overall equality of women in our organizations.

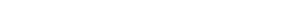

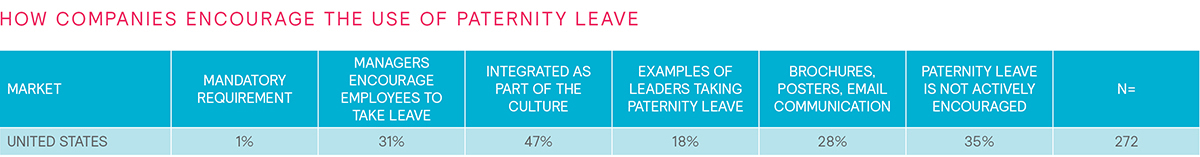

Figure 1. Source:

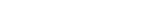

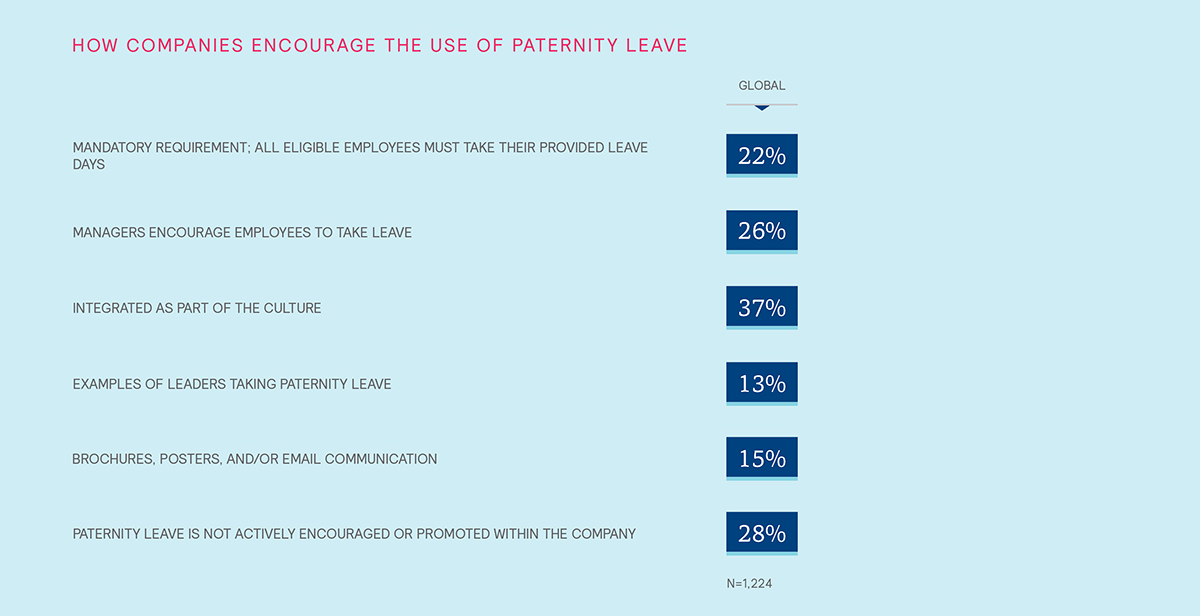

Figure 1. Source:  Figure 2. Source: World Policy Analysis Center at UCLA's Fielding School of Public Health

Figure 2. Source: World Policy Analysis Center at UCLA's Fielding School of Public Health Figure 3. Source:

Figure 3. Source:  Figure 4. Source:

Figure 4. Source: